Method Overview

This analysis method is about as basic as you can get. I used Python code to count each time an individual word appeared in the texts. The result was a total count for each searched-for word in each issue. I entered these words in a spreadsheet and normalized them to a count of how many times the word appeared per 1000 words in each issue so that I could reliably compare issues of varying lengths. I then used the spreadsheet data to graph use of words over time.

I split my keywords into thematic groups, such as words related to hazards or words related to health, both for ease of processing and to see if I could identify patterns within word families over time. My five categories were:

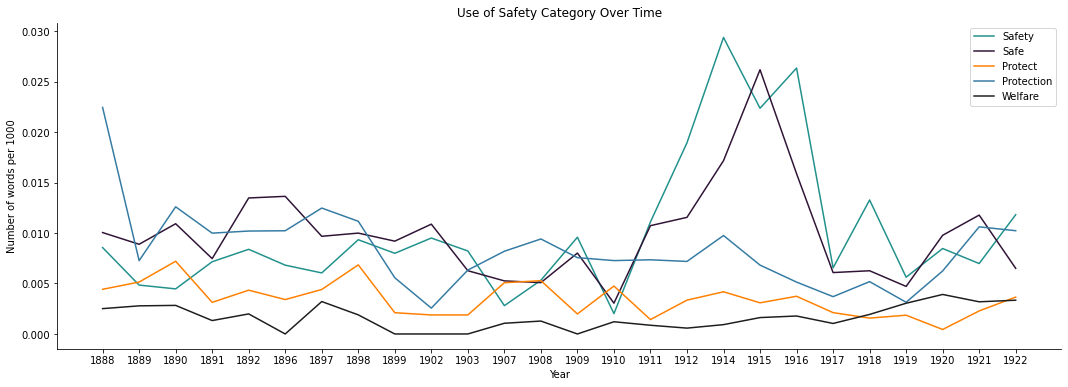

Safety words associated with safety and safety measures: safe, safety, protection, protect, welfare, safeguard, safeguards, avert, prevent, wellbeing, guard, and avoid.

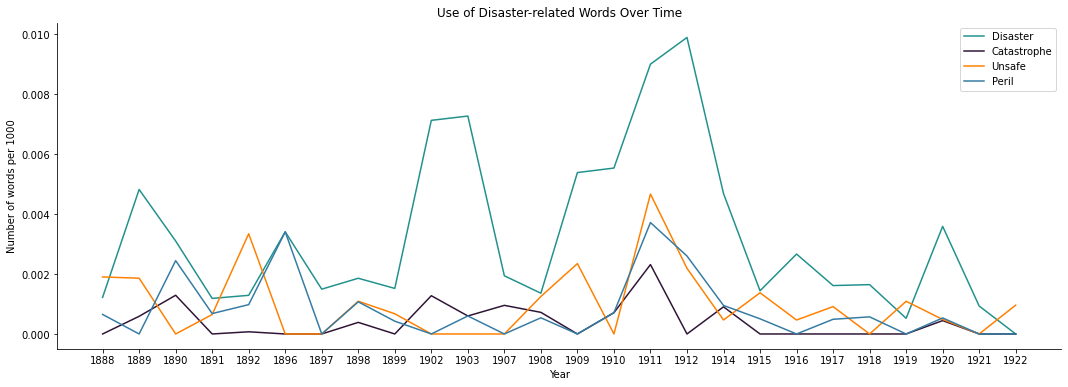

Danger words associated with unsafe conditions and workplace hazards: unsafe, hazard, risk, peril, injury, injure, destroy, damage, accident, accidents, accidental, hurt, harm, collapse, danger, dangerous, death, fatal, fatality, catastrophe, disaster, unhealthy, and victim.

Responsibility words associated with assigning blame: liability, responsibility, compensation, negligent, negligence, neglected, neglect, and careless.

Health words, including those associated with silicosis: health, healthy, lung, lungs, dust, illness, disease, sick, consumption, phthisis, and pulmonary.

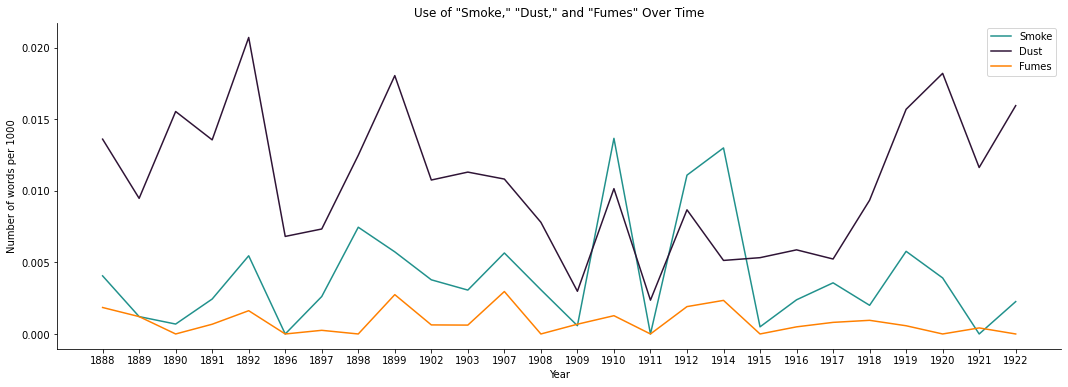

Environment words: environment, scenic, picturesque, pollution, effluence, smog, smoke, fumes, and contamination. These were hard to determine – I picked out words used in articles about the fight over the Palisades (scenic, picturesque) as well as pollutant words. I feel this is the least developed of my lists, as it is a topic I haven’t studied deeply yet.

Review of Data

I originally hoped that grouping words in categories would help me to look at big-picture patterns around families of words (like seeing responsibility or safety words being used more or less in certain time periods). However, I did not ultimately find this approach to be very helpful. As seen in the examples below, use of the words in each category were intermittent throughout time, and few patterns emerged.

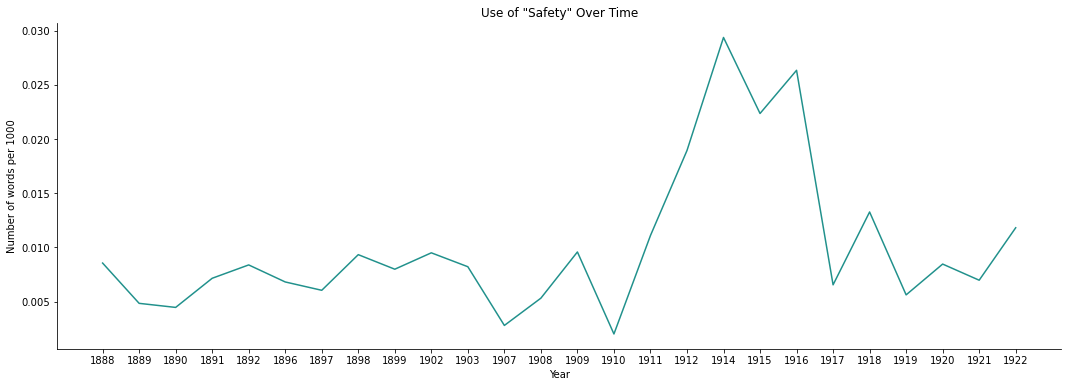

I found graphs of individual word use over time more helpful in spotting trends. Gratifyingly, “safety” was one word that shows a distinct pattern, with a significant spike in usage between 1912 and 1915.

This brings me to the limitations of this approach. While this spike shows that there was indeed an increase in the number of times this word was used in Stone during this period, does this mean that employers were paying more attention to safety in the workplace? Word frequency counts cannot provide the answer. I needed to look at the result of the keyword in context analysis to make sense of what I was seeing in the graphs above. Only by identifying the context in which the words appear could I determine that, while they are talking about safety more between 1912 and 1915, it is not typically in the context of workers’ safety or safety within stone quarrying operations. The majority of the time “safety” is used after 1910 is in the context of articles discussing concrete construction.

Reinforced concrete was a novel and experimental building material in the late 1800s, but became more prevalent in the United States in the early 1900s. The material was promoted by engineering organizations and by the American Concrete Institute, founded in 1905. The first set of national standards was published for the material by the Joint Committee on Standard Specifications for Concrete and Reinforced Concrete in 1909.[1] Concrete began to be a subject of concern to the stone industry as it started to replace the use of stone in many applications, including sidewalks (formerly an area of importance in the granite industry) and in building construction.[2] Cast stone, a concrete product similar to pre-cast concrete and referred to most frequently in the pages of Stone as “artificial stone,” joined terra cotta as a substitute for stone as an exterior cladding material. In 1904 the Bricklayers and Masons International Union (whose members were also negatively affected by the increasing use of concrete) determined to sway public opinion against concrete by publishing instances of all concrete defects found by its members.[3] While the issues from 1904-1906 have not yet been digitized, and thus I could not find a direct connection, Stone clearly followed this method in attempting to thwart what it frequently called “the advocates of cement” within its pages. Issues before 1903 occasionally mention concrete in negative terms, but issues between 1907 and 1917 directly wage war on concrete as a material, publishing article after article about failures in concrete structures or post-construction defects with dramatic titles such as “Danger in Concrete” (August 1908), “The Menace of Concrete” (October 1910), and “Concrete Claims More Victims” (December 1912). These articles appeal to architects and building commissions across the country to stop using concrete in their projects in the interest of public safety.

The most active period of Stone’s anti-concrete crusade is between 1909 and 1914. After 1914 anti-concrete articles and reports of concrete disasters continue to appear in the journal, but not with the frequency found during the earlier period. Anti-concrete articles contribute to trends in several of the other word counts, particularly for words referring to hazardous conditions which also peak in the 1909-1914 period.

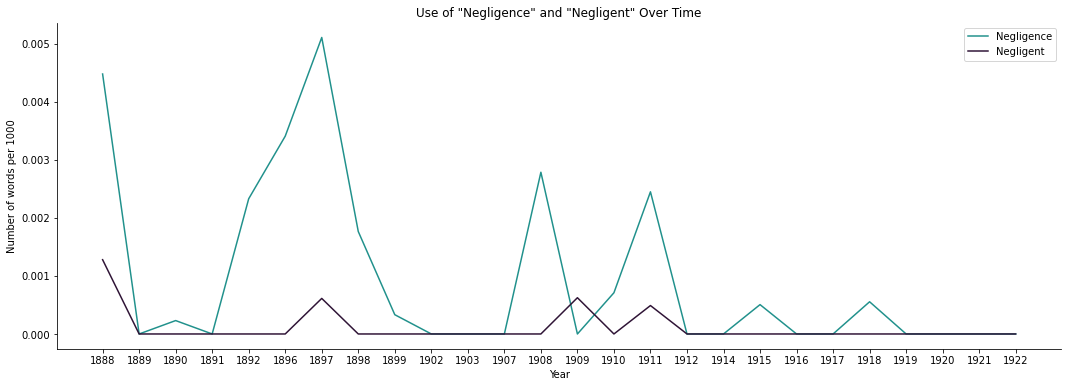

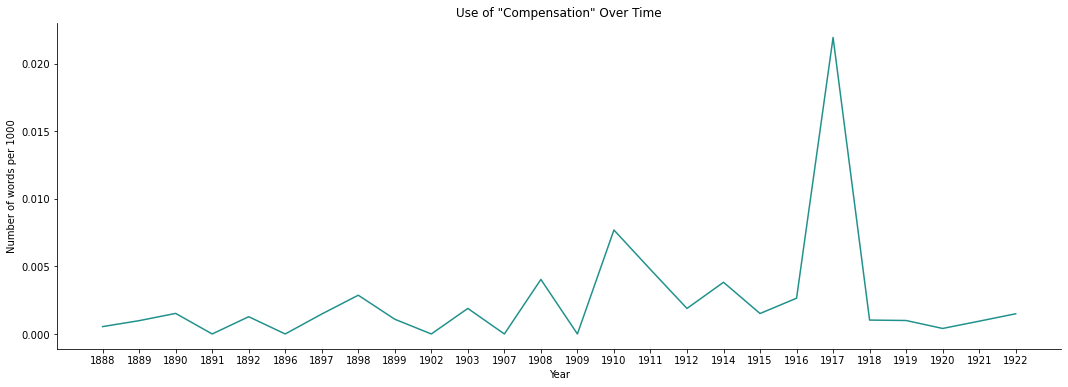

Word frequency over time did pull out a few other patterns that could be confirmed through reading the articles found in the keyword in context exercise. “Negligence” and “negligent” as used in reference to accidents caused by workers appear more frequently in the early issues of the journal. After the 1910s those terms rarely appear, and when they do it is often in reference to “concrete advocates.” “Compensation” does not appear frequently until after 1909 and is usually found in the context of articles on the effects of workmen’s compensation laws.

My lists of health and environment keywords did not show many recognizable patterns. I was hoping I would see more instances of “dust” and “lungs” on my health list. Historic literature indicates that silicosis was only beginning to enter public consciousness in the late 1910s and 1920s[4] and digitized issues are only available up to 1922. Terms associated with silicosis such as “phthisis” and “consumption” appear infrequently. Environment-related words on my list had low numbers overall and did not have any patterns I could identify.

The most surprising finding is the low number of word matches in general. Most of my words are relatively rare. For example, “safety” was pulled out only 561 times total in a corpus that contains approximately 40 million words. Several words from my original keyword lists, such as “wellbeing” didn’t appear at all. I have a suspicion that OCR problems may have something to do with this in that mis-translated versions of my keywords are present but weren’t pulled out by my searches. I did not perform preprocessing that would remove hyphens from the text and reconstruct the hyphenated words, so line breaks in the middle of my target words (for example “acci-dent”) mean those words would not be picked up. I did not stem words to their base root, which might have found additional instances, but which I feared might remove nuance from my results. Rarity also has to do with the total number of words, and I believe the large number of total words in each issue includes a lot of nonsense OCR-generated words. My words may actually be less rare than they appear. It does seem, however, that the journal spends a lot more time discussing stone markets and products rather than safety or health.

Conclusions and Areas for Further Research

As noted above, the major limitation of this approach is the lack of context for how the words are used, and thus patterns are meaningless until the context can be determined. “Death,” for instance, was most frequently used in the context of stone quarry owner obituaries rather than in accident reporting, so results related to that word over time turned out to not be particularly relevant to my research interests. Where this technique was successful, however, was in locating words I could then apply to the keyword in context search. It is a much quicker method of finding words than the keyword in context method, and being able to determine that a word is used or not used through this method definitely represents a time-savings. This method also provides a way of looking at patterns aren’t easy to visualize through the keyword in context method, but only if the results from the keywords in context analysis confirm that the words are being used in the way you imagine.

Footnotes

[1] Donald Friedman, Historical Building Construction: Design, Materials & Technology (New York: W.W. Norton Company, 1995), 105-106.

[2] Donna-Belle Garvin, “The Granite Quarries of Rattlesnake Hill: The Concord, New Hampshire, “Gold Mine.” The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 20, no. 1/2, IA IN NEW HAMPSHIRE (1994): 62.

[3] Amy E. Slaton, Reinforced Concrete and the Modernization of American Building, 1900-1930 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 156.

[4] David Rosner and Gerald E. Markowitz, Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the Politics of Occupational Disease in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), 38-42.