Method Overview

Word vector analysis is more complicated than the other two methods I used in this project. For this project I made Word2Vec SkipGram models using a Python toolkit. Word2Vec models transform a word within a document into a vector in space. Spatial relationships between words can then be represented mathematically (through math done for me by the model). The model determines how often words co-occur or are located near one another within the text and allow those contextual relationships to be expressed. Querying the model allows for the identification of semantic relationships between a keyword and other words that are used within similar contexts. There is a lot going on inside the model that is beyond my ability to reproduce on my own. However, I hoped that by looking at the word vector results in combination with keyword in context searches I could uncover why the model was making particular connections between words.

I made three models. For the first model I used all 266 issues of the journal. Because I was interested in whether language around safety changed over time, I also made two smaller models. One model used issues from 1888 through 1910 (the “to1910” model), and the other used all issues from 1911- 1922 (the “post1910” model). Due to the missing issues these two models were roughly the same size – about 20 million words each. I then looked at several of my key words in these models to see what other words were used in the same semantic context.

Review of Data

I appreciated the word vector analysis method for its provision of a different window through which to look at the text. Trying to figure out why words appeared as “similar” to my key terms involved close reading of multiple articles over long time periods to tease out relationships that were not always direct. Sometimes, as in the case of “health,” described below, I couldn’t adequately explain relationships through article text alone and had to look at the structure of the journal in a new way.

Safety

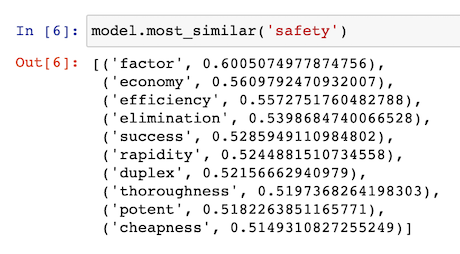

The top ten results for words used in a context most similar to the word “safety” in all issues of Stone are:

The number to the right of each word is its cosine similarity, which is a measure of how close in space the words are to one another. The number will be between 0 and 1. The closer to 1 the value is, the more often the word is found in the context of the search term. A more mathematically-based explanation for this value I found helpful can be found here.

“Factor” is the word most closely associated with “safety” in Stone. This makes sense, as a “safety factor” is an engineering term used frequently throughout the text. I was interested to see “efficiency” and “economy” having such a close relationship to “safety.” Reading through the articles found in the keyword in context analysis I found safety is often paired with efficiency, which is borne out in the literature of the “Safety First” movement, which frequently paired the two together.[1] This article, “Care in the Quarries” from the March 1917 issue includes the following representative passage:

The nation-wide campaign for “Safety First” and the turning of attention on the part of manufacturers and producers to efficiency, all tend toward a strenuous effort to reduce the percentage of accidents.[2]

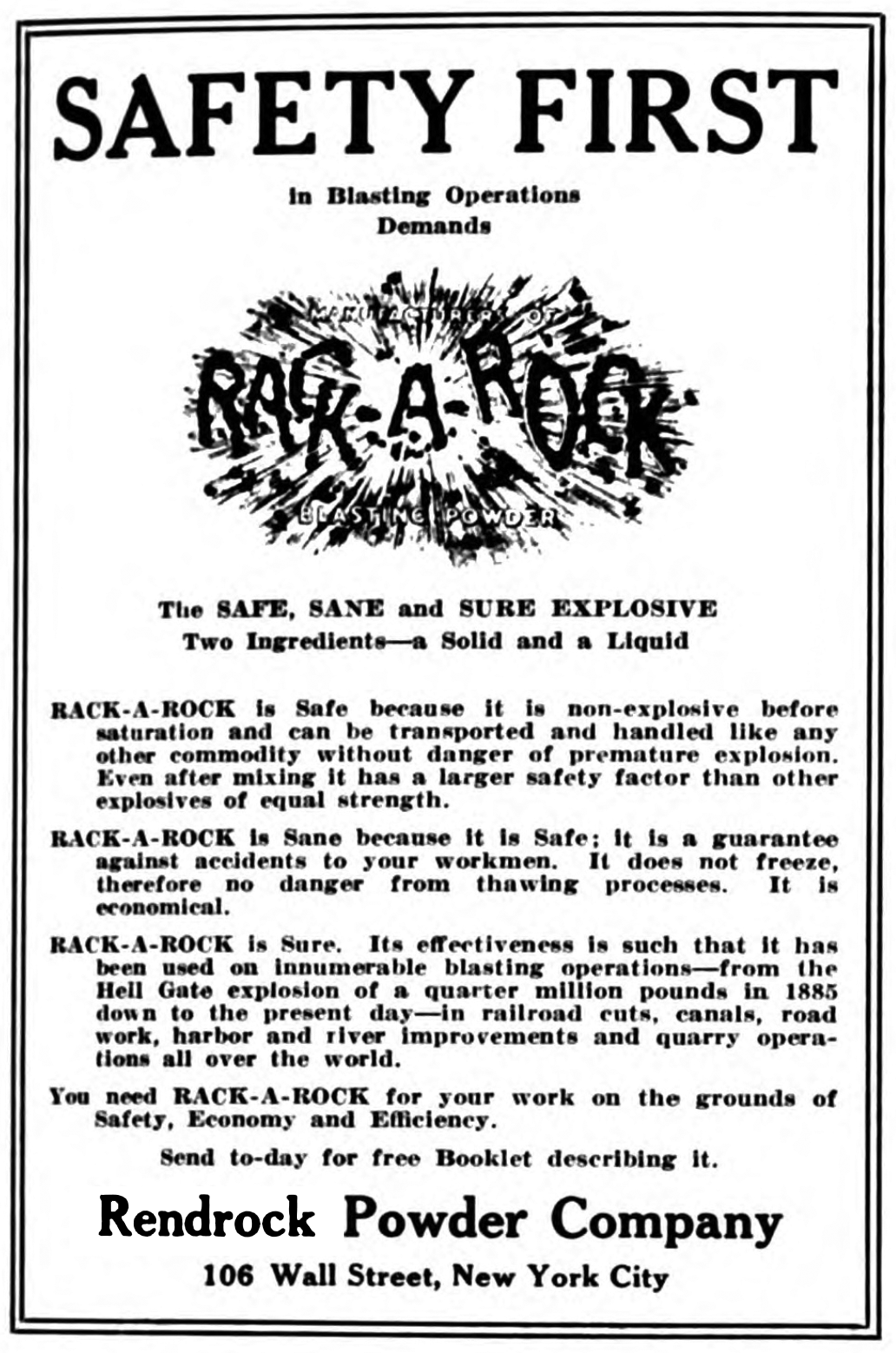

What I believe is tying “efficiency” and “economy” most strongly to “safety,” however, is advertisements. The three words appear together in an advertisement for Rack-A-Rock blasting powder which appeared in multiple issues throughout the 1910s (image below).[3] This advertisement stated, “You need Rack-A-Rock for your work on the grounds of Safety, Economy and Efficiency.”

Another advertisement, for the “Knox System of Blasting Rock,” appears frequently in the 1800s and pairs only “safety” and “economy.” The repeated presence of the Knox system’s catchphrase – “For Speed, Safety, Simplicity and Economy It Has No Rival” – might help explain why “economy” is slightly more closely matched to “safety” than “efficiency.”

Other words on the list, such as “duplex,” appeared to be strange terms until I ran them through the keyword in context analysis. In the early 1900s, Worthington duplex pumps and engines manufactured by New York Safety Power Co. appeared together in several issues in lists of machinery offered by the Quarrymen’s Machinery Agency. Machinery in general, especially in advertisements, often includes reference to safety valves, safety switches, and safety breaks, so machine words make sense in the context of safety.

The presence of “cheapness” on the list appears to come largely from the ongoing campaign in the journal against reinforced concrete, which was a threat to the stone business. Stone had two major approaches to fighting concrete in its pages. One method, as discussed in the word frequency analysis section of this site, was publicizing instances of concrete collapses and defects. The other approach was to stress the “cheapness” of imitation materials. This article, “The Fight Against Substitutes for Stone” from the February 1909 issue, is one of several that takes the latter approach, with the following statement regarding natural stone:

Through this medium found expression the choicest fancies and the full genius of Phidias and Praxiteles, of Vitruvius, of Michelangelo, of Bramante and Brunelleschi, of Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren, of Thorwaldsen and Canova, and the innumerable host of architects and sculptors whose works have made a priceless heritage for man. It may be asked, then, what has such a material to fear in competition with one that is mixed with shovel and hoe and poured into wooden moulds. In the ordinary condition of affairs, nothing. But potent influences have been at work. There has been insistent demand of the unthinking public for cheapness and haste, rather than for artistic effect, safety and durability.[4]

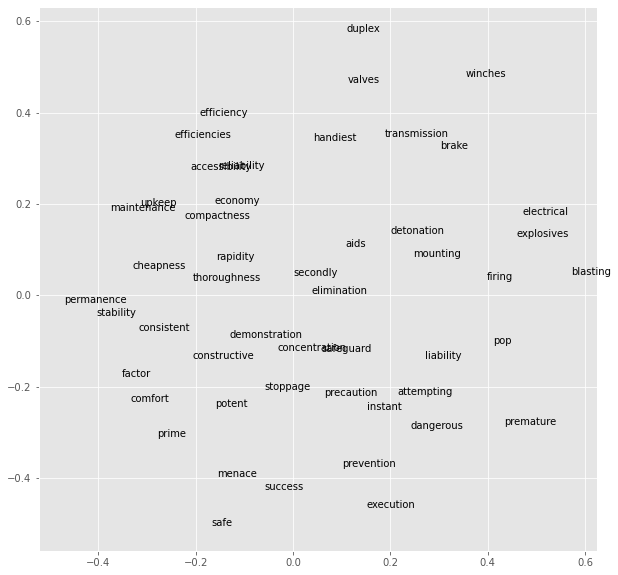

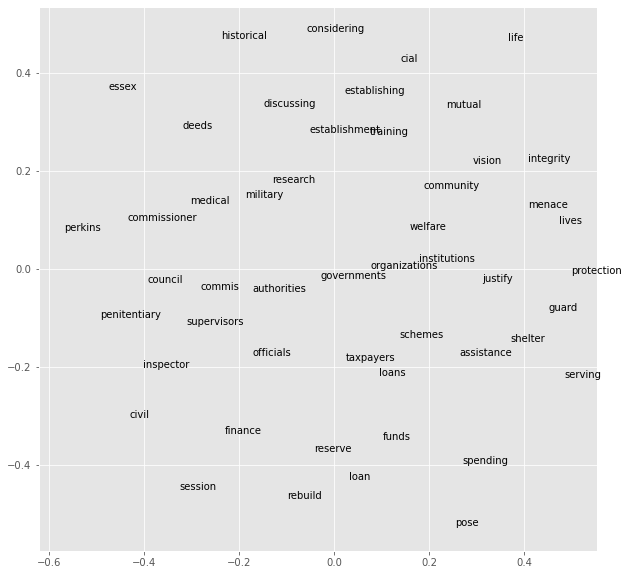

I also produced some scatterplot visualizations of these semantic relationships. While this is an oversimplified explanation, essentially these charts group multiple words associated with a keyword by their shared relationships. While all words on the graph are related to the keyword, words that are close together in the physical space of the chart are used in similar contexts in relation to the keyword and words farther apart are less likely to be used in similar contexts in relation to the keyword. For instance, all of the words on the graph below are top results in relation to “safety,” but the graph shows that articles that relate “safety” and “permanence” are different from articles that relate “safety” and “blasting”. This can let you identify semantic groups among results. The top 50 results for safety show some groupings of words from different contexts:

On the upper right of the graph is a group of words (including “duplex,” “winches,” and “brake”) associated with machinery. Much of the lower right and center is populated with words related to explosives (“pop,” “detonation,” “electrical,” “mounting,” “firing,” and “premature” among others). At the top left is a group of words I think represent the “efficiency and economy” discussion. Words at the lower left and center I believe come from the anti-concrete campaign around safety in Stone: both “permanence” and “stability” for the superior stone product and “cheapness” and “rapidity” for the inferior concrete product. “Menace” is present on the graph from the concrete-as-dangerous material side of the campaign. (There are a lot of references to “the menace of concrete” in the journal.)

The smaller 1888-1910 and 1911-1922 models have a few differences in the words most closely associated with safety over time, but in general are quite similar. Of the top ten terms closely associated with safety on the 1888-1910 list, five are explosives-related. These words include “exploder” (the top result), “maintaining” (#3), “firing,” (#4) “energy,” (#9) and “dynamo” (#10). “Vibration,” the second most similar result, is a word I believe reflects the articles that discuss the safety of the stone product itself. This kind of safety involves how to protect stone from damage during the extraction process and is often tied to use of explosives. Five of the top ten terms from the 1911-1922 model’s list of most similar terms also relate to explosives. “Efficiency” (#3) and “economy” (#4) are both on this list as well and are not present on the 1888-1910 list.

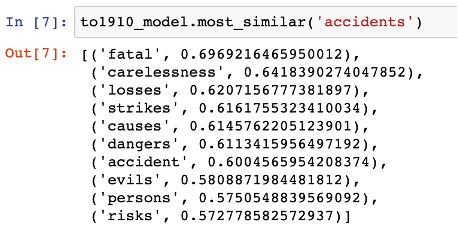

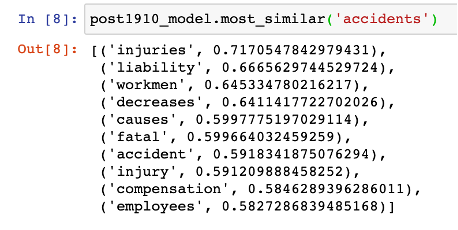

Words used in a similar context to “accidents” did show some key differences between the early journal issues and late journal issues:

The 1888-1910 list includes “carelessness” as its second most similar term, which is part of articles and accident reports that discuss worker negligence as a hindrance to workplace safety. I was interested to see “strikes” on this list. While I have not (yet) found articles in those issues that directly link safety and strikes, my suspicion is the result comes from the miscellaneous “Notes from Quarry and Shop” section that appears in each journal issue. This section provides short accident reports and quarry news items (like mentions of strikes) in the same location.

Both “workmen” and “compensation” appear on the 1911-1922 list indicating the increasing importance of relevant legislation in shaping views around safety. “Liability” and “employees,” as well as “decreases” and “causes,” I also believe come from articles discussing workmen’s compensation, methods of increasing workplace safety, and Bureau of Labor safety statistics.

Because my words don’t appear all that frequently in the text, I did not have much success moving beyond similarity of meaning. When I tried more complicated searches for multiple words or different meanings, very few results had cosine similarity numbers over 0.4 which is a sign that those vectors are not very reliable.

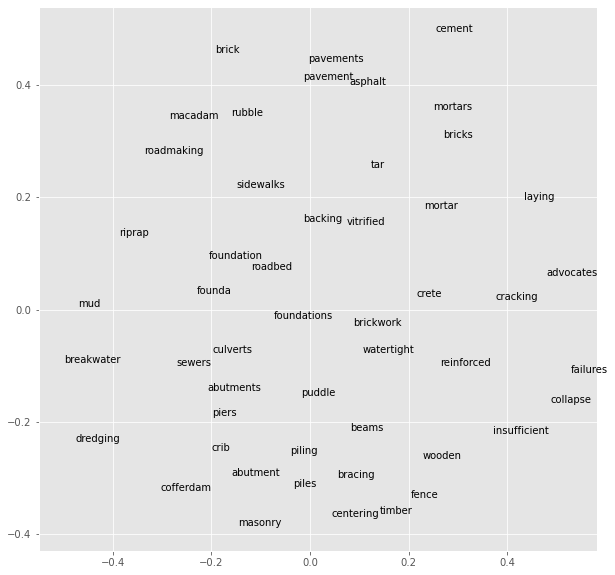

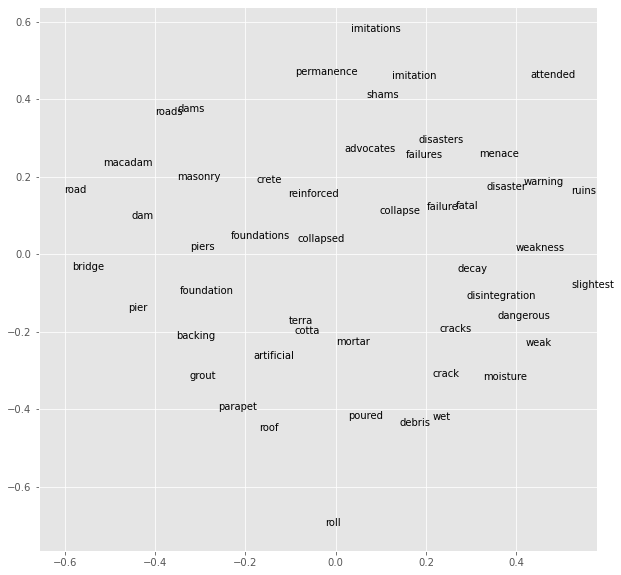

Because of its connection to safety, I was curious to see how the discussion around concrete was represented in word vector analysis. To this end I also created scatterplots for “concrete” within the two time-based models. I found the results for these two models quite interesting in their differences.

Words in the 1888-1910 corpus associated with concrete are most often related to structures typically made with concrete, for instance “foundation,” “piers,” “culverts,” and “sewers.” Part of this area of concrete structure-related words includes a large cluster of words related to seawall construction such as “breakwater,” “riprap,” “dredging,” “and “cofferdam.” Terms involving road and sidewalk construction, where concrete and asphalt/macadam were beginning to compete with stone, but also where crushed stone was often used in roadbed construction (and why I think “rubble” appears near those words), take up much of the top of the grid. The lower right-hand side of the grid (including “failures,” “collapse,” “advocates,” and “insufficient”) I believe is representative of the “concrete-as-dangerous-material” side of the anti-concrete campaign that began in the pages of the journal in the early 1900s. Concrete construction terms like “bracing” and “centering” are in the middle of the “things-you-can-make-with-concrete” and “concrete-as-dangerous-material” groups, as they are mentioned in both types of articles.

The 1911-1922 model shows how thoroughly the anti-concrete campaign has taken over in reference to concrete in the pages of Stone by 1911. Most of the words in the center and right-hand side of the graph (“collapsed,” “crack,” “failures,” “weak,” etc.) are disaster or defect-related words from the “concrete-as-dangerous-material” argument. The “concrete-as-aesthetically-inferior” side of the campaign is also present at the upper right, with words such as “imitation,” permanence,” and “shams.” “Terra cotta,” a clay material that competed with natural stone in this same period, is also present in this list of related terms, near the word “artificial.”

Health and Environment

Because my health and environment keywords were typically rarely used within the pages of the journal, I did not get reliable vector results for most of my terms. “Health” was a term that did appear somewhat frequently. I thought that the two smaller models had some interesting, and very different, groups of words that showed a change in the association of the word over time. However, the process of trying to figure out how those words came to be associated showed me how difficult it can be to interpret the results of this method.

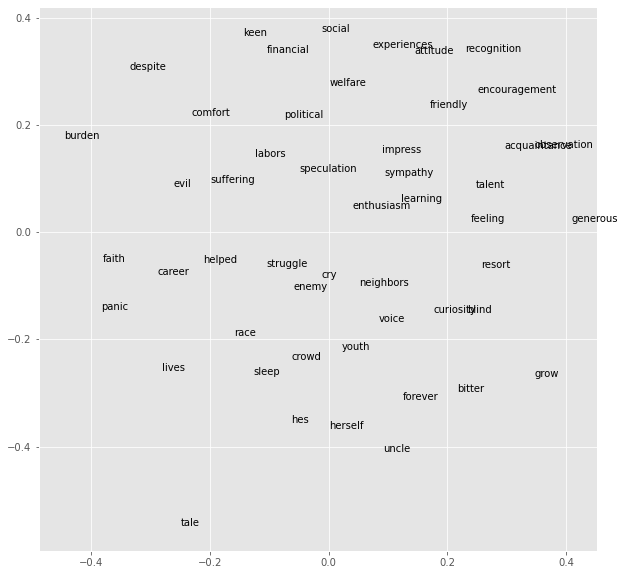

Words associated with “health” in the 1888-1910 corpus (as seen in the graph below) include a lot of emotional and value-judgement words as well as quite a few words related to family relationships. These words are not typically seen in the top words included in the 1911-1922 corpus graph. Surprisingly, “neighbors” was the word with the highest cosine similarity to “health” in the 1888-1910 corpus.

After reading through the articles I found through the keyword in context analysis for “health,” I was still unsure where the association of these words might be coming from. I then ran several other words, such as “neighbors,” “struggle,” “suffering,” “enemy,” and “evil” through the keyword in context analysis. Based on those results, I think some of this language comes from a campaign in the magazine throughout the 1800s to encourage the formation of trade associations of marble and granite dealers in various states. For instance, this editorial letter to dealers in Ohio in the February 1889 issue includes the following statement that contains several of the health-associated words:

This is the time for organization. It is the organized trades that are prosperous. It is the unorganized trades that are now doing the grumbling. There can be no positive action where there is no harmony of purpose. The trade individually concedes there is something wrong somewhere. Every man is able perhaps to locate the evil that afflicts him most. But he is helpless himself to overcome it. His neighbor is like unto himself. Did it ever occur to you that together you might smash the Pandora box and exterminate every wicked thing it contains, if everybody, or even a safe majority, took a hand in the massacre? It can be done. Any organized trade can do it. Dealers in Ohio try it.[5]

A letter printed in the “Correspondence” section of the same issue uses a similar emotional appeal (and accompanying slightly mangled Biblical reference) to explain why stone dealers should form associations with a direct connection to health:

To be able to fill the demands in this line of industry in this present age, it takes time and study. You cannot do it by using the mallet and chisel alone, you must know the material. Old men look over your past life of twenty, thirty or forty years of labor at the business. Tell us what you have accomplished. Tell us if you are still pounding, and not reading just such literature as STONE is presenting, which is putting a new phase on the whole matter pertaining to business. “Why,” one says, “we have been in the dark all this time; we have been wasting our time in the business….” Still another says “Well, let that be as it may, I beat my competitor, but it kept me poor and injured my health; I could not keep and educate my children as I wished to do, but there was no way out I was kept tied down to make both ends meet.” The times demand a close study of the saying of one of old: “No man liveth unto himself.”[6]

A lot of the terms at the top of the scatterplot appear to be from articles, letters, and editorials that were part of this campaign. However, I also have a suspicion that the structure of the journal itself contributed to relationships between words, with some of the shared terms influenced by the “Notes from Quarry and Shop” and other miscellaneous sections of each journal issue. In these miscellaneous sections, small reports of bizarre accidents co-exist with random pieces on topics of interest, jokes, short poems, announcements of new quarries, obituaries, and notices that people have sold or closed their businesses due to poor health.

The words associated with “health” in the 1911-1922 corpus (see the graph above) are very different from those of the 1888-1910 corpus. Instead of emotional words, they have become largely governmental and institutional words. A small group of words on the right side of the graph (“menace,” “lives,” “integrity,” and “guard,” among others) appear to come from the anti-concrete campaign. There is also a small cluster of words reflecting a series of articles about the “health of the industry” due to a war-related decline in building construction and discussions of how the government should intervene. This group can be found at the lower right of the graph and includes “finance,” “session,” “loans,” “taxpayers,” and “spending.”

The 1911-922 period does see a lot more discussion of public health commissions and health inspectors in the pages of the journal. However, I believe much of the change in associated words is reflective of a change in the structure of the miscellaneous news sections of the journal. The news section becomes less filled with poetry, anecdotes, and reports of strange accidents. This was a conscious decision, as the June 1909 issue announced that Stone was making some changes to its format “in response to suggestions from the leading producers and workers of stone.”[7] The “Quarrying” section (formerly “Notes from Quarry and Shop”) changed its name to “Notes from the Stone Fields” and became much more business-focused, with small news articles divided into different sections within the stone industry. The word with the greatest association to “health” in the 1911-1922 corpus is “mutual.” When I ran “mutual” through the keyword in context analysis the word appeared almost always in the context of mutual life insurance buildings. These buildings appear throughout the text in four places: in brief notes in “Notes from the Stone Fields,” in photo captions of stone-clad life insurance buildings spread out within miscellaneous sections, in the “Construction Notes” (formerly “Contract News”) section, and in advertisements that list completed projects that used a particular stone. Many of the unusual words at the left side of the graph such as “essex” and “perkins” also appear primarily in these miscellaneous sections and advertisements as part of architecture firm names and in the names of buildings that used or were considering using stone.

Conclusions and Areas for Further Research

I thought this analysis technique was an interesting way to see relationships between words in the text and gave me some new areas for research. In general, however, I worried about the level of personal interpretation I had to do to relate the words to one another as shown in my attempts to interpret the context of “health” above. I felt that splitting the model in half by date made the data more comprehensible, and more illuminating of the change over time I was looking for in my research than the single model analysis.

I’d be interested in experimenting more with word embeddings; I’d like to look more closely at some of the associations between safety and gender I was seeing in the early safety articles. I have seen other projects in which the researcher has assigned negative and positive values to words and think that would be a good next step for this project. I worry that the rarity of my words might make those investigations as unsuccessful as my attempts to work with groups of words within this analysis technique. I do think this is a useful technique, and a great way to look at the text as a whole as opposed to as a series of individual words, but only when combined with keyword in context searches to see how these connections are being made.

Footnotes

[1] Dianne Bennett and William Graebner, “Safety First: Slogan and Symbol of the Industrial Safety Movement,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 68, no. 3 ( June 1975), 250.

[2] “Care in the Quarries,” Stone 38, No. 3 (March 1917), 201.

[3] Image Source: Stone 38, No. 4 (April 1914), 213.

[4]“The Fight Against Substitutes for Stone,” Stone 29, No. 9 (February 1909), 402.

[5] Stone 1, No. 10 (February 1889), 243.

[6] “Correspondence,” Stone 1, No. 10 (February 1889), 250.

[7] Stone 30, No. 1 (June 1909), 27.